In Michael Mauboussin’s December 2007 Mauboussin on Strategy, “Death, Taxes, and Reversion to the Mean; ROIC Patterns: Luck, Persistence, and What to Do About It,” (.pdf) Mauboussin provides a tour de force of data on the tendency of return on invested capital (ROIC) to revert to the mean. Much of my investing to date has been based on the naive assumption that the tendency is so powerful that companies with a high ROIC should be avoided because the high ROIC is not sustainable, but rather indicates a cyclical top in margins and earnings. This view is broadly supported by other research on mean reversion in earnings that I have discussed in the past, which has suggested, somewhat counter-intuitively, that in aggregate the earnings of low price-to-book value stocks grow faster than the earnings of high price-to-book value stocks. I usually cite this table from the Tweedy Browne What works in investing document:

In the four years after the date of selection, the earnings of the companies in the lowest price-to-book value quintile (average price-to-book value of 0.36) increase 24.4%, more than the companies in the highest price-to-book value quintile (average price-to-book value of 3.42), whose earnings increased only 8.2%. DeBondt and Thaler attribute the earnings outperformance of the companies in the lowest quintile to mean reversion, which Tweedy Browne described as the observation that “significant declines in earnings are followed by significant earnings increases, and that significant earnings increases are followed by slower rates of increase or declines.”

Mauboussin’s research seems to suggest that, while there exists a strong tendency towards mean reversion, some companies do “post persistently high or low returns beyond what chance dictates.” He has two caveats for those seeking the stocks with persistent high returns:

1. The “ROIC data incorporate much more randomness than most analysts realize.”

2. He “had little luck in identifying the factors behind sustainably high returns.”

That said, Mauboussin presents some striking data about “persistence” in high ROIC companies that suggests investing in high ROIC companies is not necessarily a short ride to the poor house, and might actually work as an investment strategy. (That was very difficult to write. It goes against every fiber of my being.) Here’s Mauboussin’s research:

Mauboussin’s report has three broad conclusions, with significant implications for modelling:

- Reversion to the mean is a powerful force. As has been well documented by numerous studies, ROIC reverts to the cost of capital over time. This finding is consistent with microeconomic theory, and is evident in all time periods researchers have studied. However, investors and executives should be careful not to over interpret this result because reversion to the mean is evident in any system with a great deal of randomness. We can explain much of the mean reversion series by recognizing the data are noisy.

- Persistence does exist. Academic research shows that some companies do generate persistently good, or bad, economic returns. The challenge is finding explanations for that persistence, if they exist.

- Explaining persistence. It’s not clear that we can explain much persistence beyond chance. But we investigated logical explanatory candidates, including growth, industry representation, and business models. Business model difference appears to be a promising explanatory factor.

ROIC mean reversion

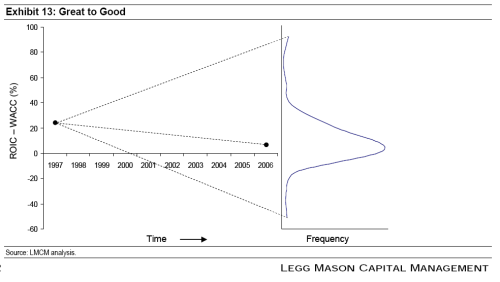

Here Mauboussin charts the reversion-to-the-mean phenomenon using data from “1000 non-financial companies from 1997 to 2006.” The chart shows a clear trend towards nil economic profit, as you would expect:

We start by ranking companies into quintiles based on their 1997 ROIC. We then follow the median ROIC for the five cohorts through 2006. While all of the returns do not settle at the cost of capital (roughly eight percent) in 2006, they clearly migrate toward that level.

And another chart showing the change:

Mauboussin has this elegant interpretation of the results:

Mauboussin has this elegant interpretation of the results:

Any system that combines skill and luck will exhibit mean reversion over time. 7 Francis Galton demonstrated this point in his 1889 book, Natural Inheritance, using the heights of adults. 8 Galton showed, for example, that children of tall parents have a tendency to be tall, but are often not as tall as their parents. Likewise, children of short parents tend to be short, but not as short as their parents. Heredity plays a role, but over time adult heights revert to the mean.

The basic idea is outstanding performance combines strong skill and good luck. Abysmal performance, in contrast, reflects weak skill and bad luck. Even if skill persists in subsequent periods, luck evens out across the participants, pushing results closer to average. So it’s not that the standard deviation of the whole sample is shrinking; rather, luck’s role diminishes over time.

Separating the relative contributions of skill and luck is no easy task. Naturally, sample size is crucial because skill only surfaces with a large number of observations. For example, statistician Jim Albert estimates that a baseball player’s batting average over a full season is a fifty-fifty combination between skill and luck. Batting averages for 100 at-bats, in contrast, are 80 percent luck. 9

Persistence in ROIC Data

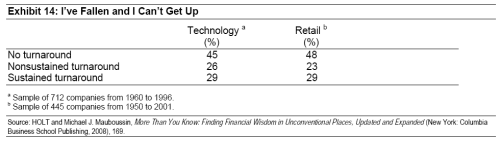

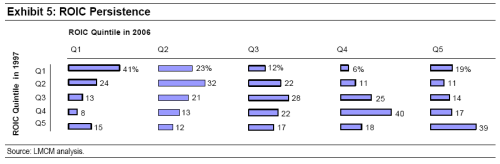

“Persistence” is the likelihood a company will sustain its ROIC. If the stocks are ranked on the basis of ROIC and then placed into quintiles, persistence is likliehood that a stock will remain in the same quintile throughout the measured time frame. Mauboussin then measures persistence by analysing “quintile migration:”

This exhibit shows where companies starting in one quintile (the vertical axis) ended up after nine years (the horizontal axis). Most of the percentages in the exhibit are unremarkable, but two stand out. First, a full 41 percent of the companies that started in the top quintile were there nine years later, while 39 percent of the companies in the cellar-dweller quintile ended up there. Independent studies of this persistence reveal a similar pattern. So it appears there is persistence with some subset of the best and worst companies. Academic research confirms that some companies do show persistent results. Studies also show that companies rarely go from very high to very low performance or vice versa. 13

These are striking findings. In Mauboussin’s data, there was a 64% chance that a company in the highest quintile at the start of the period was still in the first or second quintile at the end of the 10 year period. Further, it seems that there is a three-in-four chance that the high quintile stocks don’t fall into the lowest or second lowest quintiles after 10 years. It’s not all good news however.

Before going too far with this result, we need to consider two issues. First, this persistence analysis solely looks at where companies start and finish, without asking what happens in between. As it turns out, there is a lot of action in the intervening years. For example, less than half of the 41 percent of the companies that start and end in the first quintile stay in the quintile the whole time. This means that less than four percent of the total-company sample remains in the highest quintile of ROIC for the full nine years.

The second issue is serial correlation, the probability a company stays in the same ROIC quintile from year to year. As Exhibit 5 suggests, the highest serial correlations (over 80 percent) are in Q1 and Q5. The middle quintile, Q3, has the lowest correlation of roughly 60 percent, while Q2 and Q4 are similar at about 70 percent.

This result may seem counterintuitive at first, as it suggests results for really good and really bad companies (Q1 and Q5) are more likely to persist than for average companies (Q2, Q3, and Q4). But this outcome is a product of the methodology: since each year’s sample is broken into quintiles, and the sample is roughly normally distributed, the ROIC ranges are much narrower for the middle three quintiles than for the extreme quintiles. So, for instance, a small change in ROIC level can move a Q3 company into a neighboring quintile, whereas a larger absolute change is necessary to shift a Q1 and Q5 company. Having some sense of serial correlations by quintile, however, provides useful perspective for investors building company models.

So, in summary, better performed companies remain in the higher ROIC quintiles over time, although the better-performed quintiles will still suffer substantial ROIC attrition over time.

More to come.

Hat tip Fallible Investor.

Read Full Post »