I received a number of emails asking me to revisit the backtests from last week’s post about using the Shiller PE to time the market (Worried about a Crash? Backtests Using Shiller PE to Time The Market (1926 to 2014)). The most common request was to separate the buy and sell rules such that if the strategy sold out at say one standard deviation above the mean, it didn’t buy back until the Shiller PE fell below its mean. The second most common request was to alter the strategy such that it hedged out the market rather than switching to cash.

Edit: Fama and French backtests of the book value-to-market equity (the inverse of the PB ratio) data from 1926 to 2013. As at December 2013, there were 3,175 firms in the sample. The value decile contained the 459 stocks with the highest earnings yield, and the glamour decile contained the 404 stocks with the lowest earnings yield. The average size of the glamour stocks is $7.48 billion and the value stocks $2.54 billion. (Note that the average is heavily skewed up by the biggest companies. For context, the 3,175th company has a market capitalization today of $404 million, which is smaller than the average, but still investable for most investors). Portfolios are formed on June 30 and rebalanced annually.

The following backtests use the market’s state of knowledge at the time about the average, and standard deviations of the Shiller PE. The chart below shows how the Shiller PE’s average and standard deviations have varied over time.

Shiller PE, Average, and Plus/Minus Two Standard Deviations (1881 to Present)

The mean now is 16.55, but was as low as 14.2 in the 1950s and, excluding the slightly higher reading at the start of the data, as high as 17.5 in the 1900s. The standard deviation has expanded over time. Until the 2000s two standard deviations above the average meant a Shiller PE of about 25, and now it means a Shiller PE of almost 30.

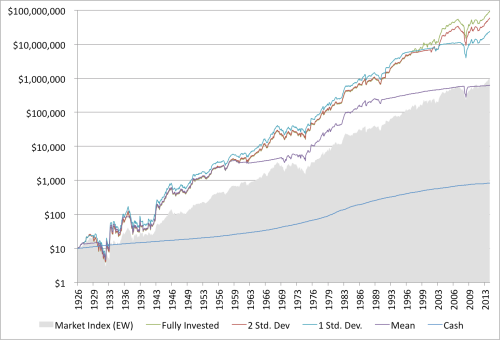

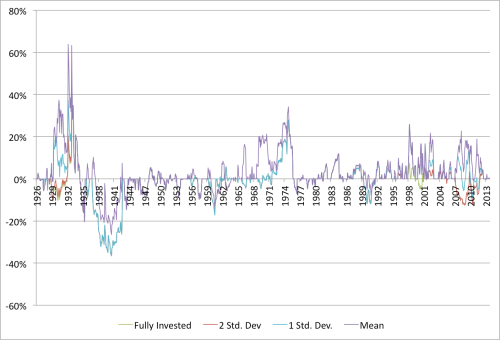

Performance of Value Decile (Price-to-Book Value), Cash and 3 Shiller PE Timed Strategies (1926 to Present)

The following chart backtests three strategies. The first–“Sell at 1SD, Buy at -1SD”–buys the price-to-book value decile only if the Shiller PE is one standard deviation below its mean, sells into cash if the Shiller PE is more than one standard deviation above its mean, and holds cash until the market falls back below one standard deviation below the mean. The second–“Sell at 1SD, Buy at Mean”–buys the price-to-book value decile only if the Shiller PE is below its mean, sells into cash if the Shiller PE is more than one standard deviation above its mean, and holds cash until the market falls back below the mean. The third–“Sell at 2SD, Buy at Mean”–buys the value decile only if the Shiller PE is below its mean, sells into cash if the Shiller PE is more than two standard deviations above its mean, and holds cash until the market falls back below the mean.

All the strategies underperform the simple buy-and-hold strategy over the full period.

The market returned 13.94 percent compound and the fully invested PB value decile returned 20 percent compound over the full period. Sell at 1SD, Buy at -1SD returned 15.0 percent compound; Sell at 2SD, Buy at Mean returned 19.3 percent compound; and Sell at 1SD, Buy at Mean returned 15.9 percent compound.

Sell at 2SD, Buy at Mean had good lead until the 1990s, but has woefully underperformed since. Notably, it is still fully invested. Its sell rule won’t kick in until the Shiller PE hits 29.7.

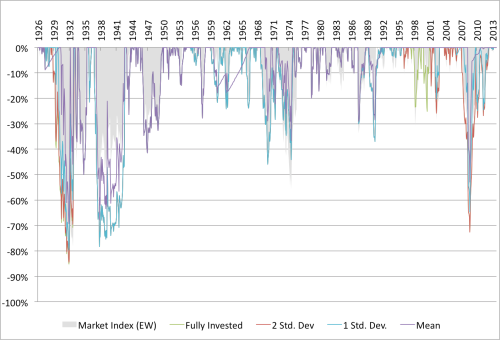

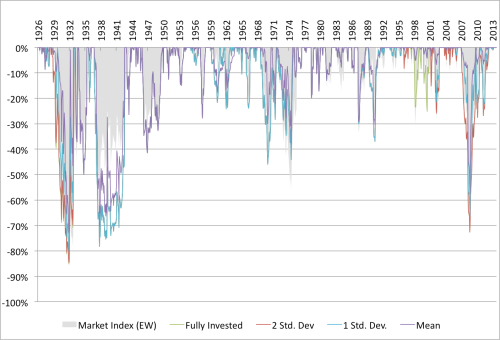

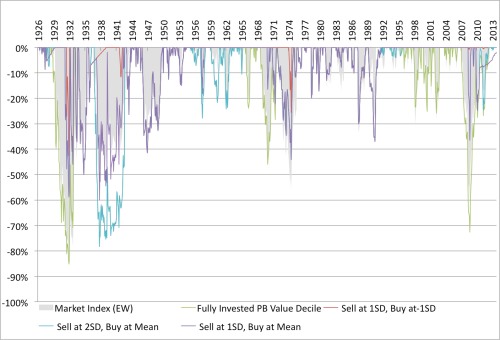

Drawdowns of Value Decile (Price-to-Book Value), Cash and 3 Shiller PE Timed Strategies (1926 to Present)

The market has the worst maximum drawdown at 86 percent, and the fully invested PB value decile has a comparably bad maximum drawdown of 85 percent. Sell at 1SD, Buy at -1SD had the best maximum drawdown at 50 percent; Sell at 2SD, Buy at Mean had a maximum drawdown of 78 percent; and Sell at 1SD, Buy at Mean had a maximum drawdown of 60 percent.

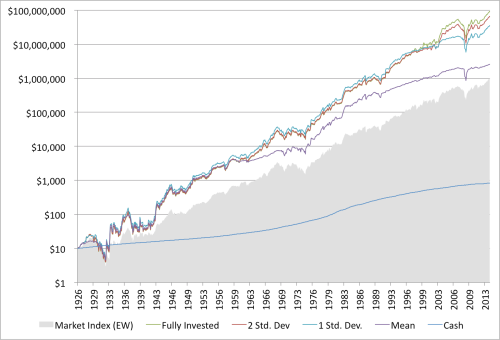

Graham Rule: Performance of Value Decile (Price-to-Book Value), Cash and 3 Shiller PE Timed Strategies (1926 to Present)

Benjamin Graham recommended maintaining a minimum portfolio exposure to stocks of 25 percent. Below we re-run the tests, but this time instead of kicking all of the portfolio into cash, we put only 75 of the portfolio in cash, and maintain 25 percent exposure to the value decile.

All the returns are improved, but the strategies continue to underperform the simple buy-and-hold strategy over the full period.

Sell at 1SD, Buy at -1SD now returns 16.8 percent compound; Sell at 2SD, Buy at Mean returned 19.6 percent compound versus 19.3 percent above; and Sell at 1SD, Buy at Mean returned 17.2 percent compound.

Graham Rule: Drawdowns of Value Decile (Price-to-Book Value), Cash and 3 Shiller PE Timed Strategies (1926 to Present)

The tradeoff for slightly improved returns is slightly worse drawdowns. Sell at 1SD, Buy at -1SD still has the lowest maximum drawdown, but now draws down 53 percent; Sell at 2SD, Buy at Mean has the same maximum drawdown of 78 percent; and Sell at 1SD, Buy at Mean had a maximum drawdown of 64 percent.

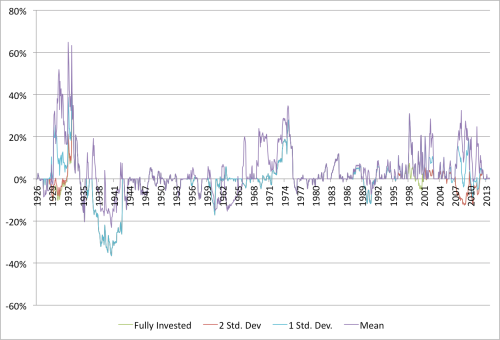

Market Hedge: Performance of Value Decile (Price-to-Book Value), Cash and 3 Shiller PE Timed Strategies (1926 to Present)

In this set of backtests the strategy is levered and hedged. The ratios change depending on the level of the market. When the strategy deems the market cheap, it is 130 percent long the value decile, and 30 short the market. When the market is expensive, it doesn’t sell into cash, but reduces the long to 100 percent, and hedges out 75 percent of the portfolio using the market.

The Hedge at 2SD, Lever at Mean strategy outperforms the buy-and-hold strategy over the full period, returning 21.9 percent compound, versus 20 percent for the value decile.

Hedge at 1SD, Lever at -1SD now returns 19 percent compound; and Hedge at 1SD, Buy at Mean returned 18.9 percent compound.

Market Hedge: Drawdowns of Value Decile (Price-to-Book Value), Cash and 3 Shiller PE Timed Strategies (1926 to Present)

The tradeoff for the improved returns is bigger drawdowns.

Hedge at 2SD, Lever at Mean strategy draws down 88 percent, worse than the market’s 85 percent; Hedge at 1SD, Lever at -1SD has a maximum draw down of 67 percent; and Hedge at 1SD, Buy at Mean has a maximum drawdown of 79 percent.

Changing the buy-and-sell rules, and hedging rather than running to cash alters the performance of the strategies. The levered and hedged strategy that maximizes exposure to the market–Hedge at 2SD, Lever at Mean–outperforms the simple buy-and-hold strategy, but does so with an enormous drawdown. Nothing else beats buy-and-hold. As we saw last week, the more conservative the Shiller PE ratio used, the lower the drawdown, but returns suffer. To generate the extraordinary returns of the value deciles I’ve examined over the last few weeks, it was necessary to remain fully invested in those value stocks through thick and thin. My firm, Eyquem, offers low cost, fee-only managed accounts that implement a systematic deep value investment strategy. Please contact me by email at toby@eyquem.net or call me by telephone on (646) 535 8629 to learn more. Click here if you’d like to read more on Quantitative Value, or connect with me on Twitter, LinkedIn or Facebook.