Zero Hedge has an article Buy Cash At A Discount: These Companies Have Negative Enterprise Value in which Tyler Durden argues that stock market manipulation has led to valuation dislocations, and gives as evidence the phenomenon of stocks trading with a negative enterprise value (EV):

With humans long gone from the trading arena and algorithms left solely in charge of the casino formerly known as “the stock market”, in which price discovery is purely a function of highly levered synthetic instruments such as ES and SPY or, worse, the EURUSD and not fundamentals, numerous valuation dislocations are bound to occur. Such as company equity value trading well below net cash (excluding total debt), or in other words, negative enterprise value, meaning one can buy the cash at a discount of par and assign zero value to all other corporate assets.

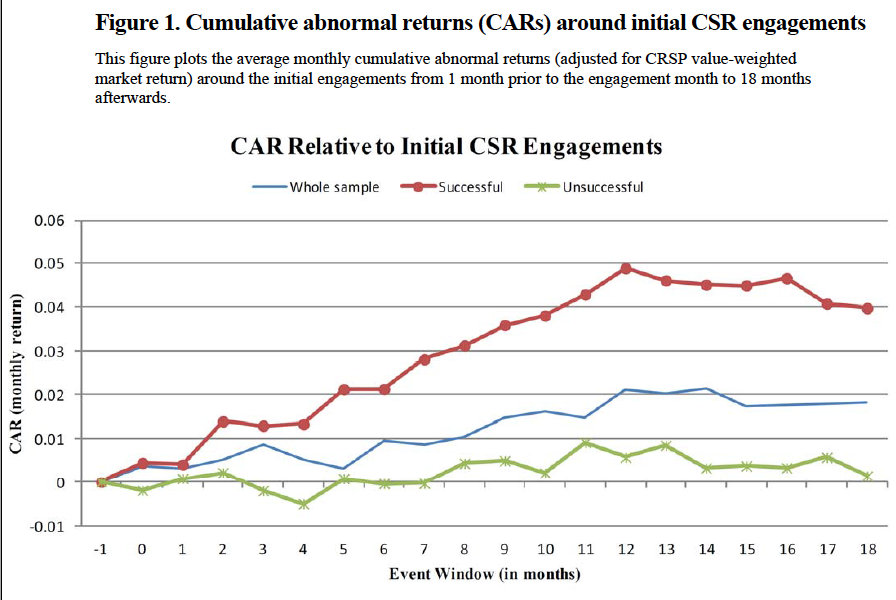

Just as the fact of your paranoia does not exclude the possibility that someone is following you*, you don’t need to believe in manipulation to believe that negative EV is a “valuation dislocation.” Negative EV stocks are often also Graham net nets or almost net nets, and so perform like net nets. For example, Turnkey Analyst took a look at the performance of negative EV stocks (click to enlarge):

Long story short: they ripped, but they were few (sometimes non-existent), and small (mostly micro), which means you would have been heavily concentrated in a few mostly very small stocks, and regularly carried a lot of cash. If you eliminated the tiniest (i.e. the smallest 10 or 20 percent), much of the return disappeared, and volatility spiked markedly. Says Wes:

A few key points:

- After you eliminate the micro-crap stocks, you end up being invested in a few names at a time (sometimes you go all-in on a single firm!)

- Sometimes the strategy isn’t invested.

- The amazing Bueffettesque returns for the “all firms” portfolio above are exclusively tied to micro-craps.

Here’s the frequency of negative EV opportunities according to Turnkey (click to enlarge):

No surprise, there were more following a crash (1987, 2001, 2009) and fewer at the peak (1986, 1999, 2007). If your universe eliminated the smallest 20 percent (the green line), you spent a lot of time in cash. If your universe was unrestricted (the red line), then you’d have had some prospects to mine most of the time. Clearly, it’s not an institutional-grade strategy, but it has worked for smaller sums.

Zero Hedge screened Russell 2000 companies finding 10 companies with negative enterprise value, and then further subdivided the screen into companies with negative, and positive free cash flow (defined here as EBITDA – Cap Ex). Here’s the list (click to enlarge):

Including short-term investments yields a bigger list (click to enlarge):

Like Graham net nets, negative EV stocks are ugly balance sheet plays. They lose money; they burn cash; the business, if they actually have one, usually needs to be taken to the woodshed (so does management, for that matter). Frankly, that’s why they’re cheap. Says Durden:

Typically negative EV companies are associated with pre-bankruptcy cases, usually involving large cash burn, in other words, where the cash may or may not be tomorrow, and which may or may not be able to satisfy all claims should the company file today, especially if it has some off balance sheet liabilities.

You can cherry-pick this screen or buy the basket. I favor the basket approach. Just for fun, I’ve formed four virtual portfolios at Tickerspy to track the performance:

- Zero Hedge Negative Enterprise Value Portfolio

- Zero Hedge Negative Enterprise Value Portfolio (Positive FCF Only)

- Zero Hedge Negative Enterprise Value (Inc. Short-Term Investments) Portfolio

- Zero Hedge Negative Enterprise Value (Inc. Short-Term Investments) Portfolio (Positive FCF Only)

I’ll check back in occasionally to see how they’re doing. My predictions for 2013:

- All portfolios beat the market

- Portfolio 1 outperforms Portfolio 2 (i.e. all negative EV stocks outperform those with positive FCF only)

- Portfolio 3 outperforms Portfolio 4 for the same reason that 1 outperforms 2.

- Portfolios 1 and 2 outperform Portfolios 3 and 4 (pure negative EV stocks outperform negative EV including short-term investments)

Take care here. The idiosyncratic risk here is huge because the portfolios are so small. Any bump to one stock leaves a huge hole in the portfolio.

* Turn around. I’m right behind you.

Read Full Post »