Cliff Asness, founder of AQR, seems to be doing the rounds lately. Forbes has a great interview with him called Efficient Market? Baloney, Says Famed Value And Momentum Strategist Cliff Asness.

Here’s Asness talking about the outperformance of value:

Forbes: Isn’t it all about probabilities? You can’t predict the future, but do you feel you can find patterns that generally hold up?

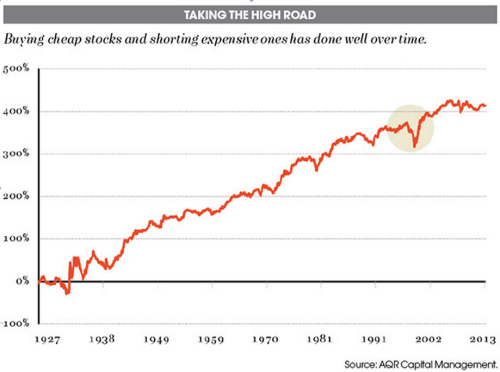

Asness: It’s all about probabilities. And I love that you put it that way. I don’t think it’s different necessarily for non-quantitative firms. We just might acknowledge it a little more explicitly. But I’m in a business where if 52% of the day I’m right, I’m doing pretty well over the long term. That’s not so easy to live with on a daily basis. I like to say, when I say a strategy works, I kind of mean six or seven out of 10 years. A little more than half the days. If your car worked like this you’d fire your mechanic. But we are playing the odds. Some famous findings, cheap stocks, defined simply, price-to-book, cash flow, sales.

You can try to do better, but define it simply. Beat expensive stocks. They beat them on average with a small margin and you want to own a ton of them and be underweight or short a ton of the expensive ones because something like this for one stock means almost nothing.

On active versus passive investment, and the central paradox of efficient markets:

Forbes: How do you defend your approach? Not in the specifics, but the whole thing on indexing. We all know Malkiel and others, Charlie Ellis, will tell you that if you have the discipline to stick to an index, low fees. Your fees are relatively high. Wouldn’t you just be better off saving all that brain power and just riding the wave?

Asness: Sure. Off the bat I’ll tell you my two investing heroes, and there are a lot of good ones to choose from, are Jack Bogle and my dissertation advisor, Gene Fama. So I can’t sit here and put down indexing too much. And in fact when I’m asked, “What advice would you give individuals who are not going to dedicate themselves to this and what not,” I tell them, “The market might not be perfectly efficient, but for most people acting as if it is,” and this is not the only way to get to an index fund, but it’s one route to get to it, it’s certainly one route that implies an index fund. I tell them to do that.

Having said that, there are a lot of ways to get here, but there’s a central paradox to efficient markets. Efficient markets says you can’t beat an index, the price contains all the information. For a long time we’ve known, academics have known, that somebody has to be gathering that information. The old conundrum: What if everyone indexed? Prices would be wildly inefficient.

So I do take what ends up being an arrogant view, and I admit it, that on average people don’t beat the index. Here are the mistakes they make. Here are the risk premiums you can pick up. I do think it’s somewhat profitable, and we want to be some of the people helping make the markets efficient and we think you get paid for that. So that is both how I reconcile it and how I sleep at night.

But if an individual came to me and said, “What should I do?” I don’t say, “Pour your money into my fund,” because, for one thing, they don’t know that much and if we have a bad year they won’t stick with it. I tell them, “Study the history a little bit, just a little bit, and put it in the most aggressive mix of stocks and bonds that you wouldn’t have thrown up and left in the past. And go to Jack Bogle to get it.”

On quantitative value as practiced by AQR:

Forbes: Quickly go over what you call the four styles of investing, starting with value.

Asness: …

And that’s kind of the holy grail of investing. To find various investments, of course, and I know you know this, that go up over time — there’s no substitute for going up — but that go up at different times.

To us, the academic literature has produced a ton. If you want to be a cynic, they’ve produced too many. A lot of smart people with even smarter computers will turn out a lot of past results and we have hundreds of different effects. The blank effect. The silliest ones are things like the Super Bowl, the sunspot effect.

But when someone searches every piece of data and it’s not that silly, it involves an accounting variable, even if ultimately it’s silly when you drill down, it’s harder to dismiss. What we did was kind of almost a self examination of going through and saying, “Of all these things we’ve been reading about for years, many of which we’ve been implementing, if we had to bet the ranch,” now we’re quant, so we never bet the single ranch on anything but over the long-term, if we had to really say, “What are the biggies that we would be most confident in?” They have to have worked for the long term. Data still counts. They need to have great intuition. They have to have worked out of sample, that thing I was talking about before, after they’ve been discovered. If they were discovered in 1970, how’d they do after that? A telltale sign of something that was dredged out of the data is discovered in 1970. Wonderful for the first 70 years of the century and terrible for the last 30 years.

And it has to be implementable. Meaning, there are some things that academics and others look at that when you try with real world transactions cost in a real world portfolio, you find, “Gee, gross, I made a lot of money but net Wall Street made a lot of money. I didn’t make a lot of money.”

Came down to four. Value. Cheap beats expensive. Famous is in U.S. stocks. For me it’s very related to Graham and Dodd value. It’s the same intuition. But where most Graham and Dodd investors will use it to pick a handful of stocks we’ll say the thousand cheapest on our favorite measures will beat the thousand most expensive. We’re betting on a concept more than a specific firm, but looking for the same ideas.

…

I still think of value as the hero of the story. You’re a manager long cheap and short expensive. I’m the momentum heretic. I’m long good momentum, short bad momentum. A good year for you is usually not my best year. Think about it. It works in the math but also in spirit. When value’s being rewarded you would not think it’s a particularly good time for momentum.

If there’s any magic to the finding, and I’m still amazed by it, is while we hedge each other a bit, more than a bit, both of us make money if we follow it with discipline over time.

Read Forbes’ Efficient Market? Baloney, Says Famed Value And Momentum Strategist Cliff Asness.

Click here to read earlier articles on Asness, AQR’s Value Strategies In Practice or On The Great Shiller PE Controversy: Are Cyclically-Adjusted Earnings Below The Long-Term Trend?.

Click here if you’d like to read more on Quantitative Value, or connect with me on LinkedIn.