My piece on S&P 500 forward earnings estimates and the overvaluation of the market generated a number of heated emails and comments. I didn’t know that it was so controversial that the market is expensive. I’m not saying that the market can’t continue to go up (I’ve got no idea what the market is going to do). My point is that there are a variety of highly predictive, methodologically distinct measures of market-level valuation (I used the Shiller PE and Tobin’s q, but GNP or GDP-to-total market capitalization below work equally as well) that point to overvaluation.

The popular price-to-forward operating earnings measure does not point to overvaluation, but is flawed because forward operating earnings are systematically too optimistic. It’s simply not predictive, mostly because it fails to take into account the highly mean reverting nature of profit margins. Here’s John Hussman from a week ago in his piece Investment, Speculation, Valuation, and Tinker Bell (March 18, 2013):

From an investment standpoint, it’s important to recognize that virtually every assertion you hear that “stocks are reasonably valued” is an assertion that rests on the use of a single year of earnings as a proxy for the entire long-term stream of future corporate profitability. This is usually based on Wall Street analyst estimates of year-ahead “forward operating earnings.” The difficulty here is that current profit margins are 70% above the long-term norm.

…

Most important, the level of corporate profits as a share of GDP is strongly and inversely correlated with the growth in corporate profits over the following 3-4 year period.

While I believe the Shiller PE and Tobin’s q to be predictive, there are other measures of market valuation that perform comparably. Warren Buffett’s favored measure is “the market value of all publicly traded securities as a percentage of the country’s business–that is, as a percentage of GNP.” Here he is in a 2001 interview with Fortune’s Carol Loomis:

[T]he market value of all publicly traded securities as a percentage of the country’s business–that is, as a percentage of GNP… has certain limitations in telling you what you need to know. Still, it is probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment. And as you can see, nearly two years ago the ratio rose to an unprecedented level. That should have been a very strong warning signal.

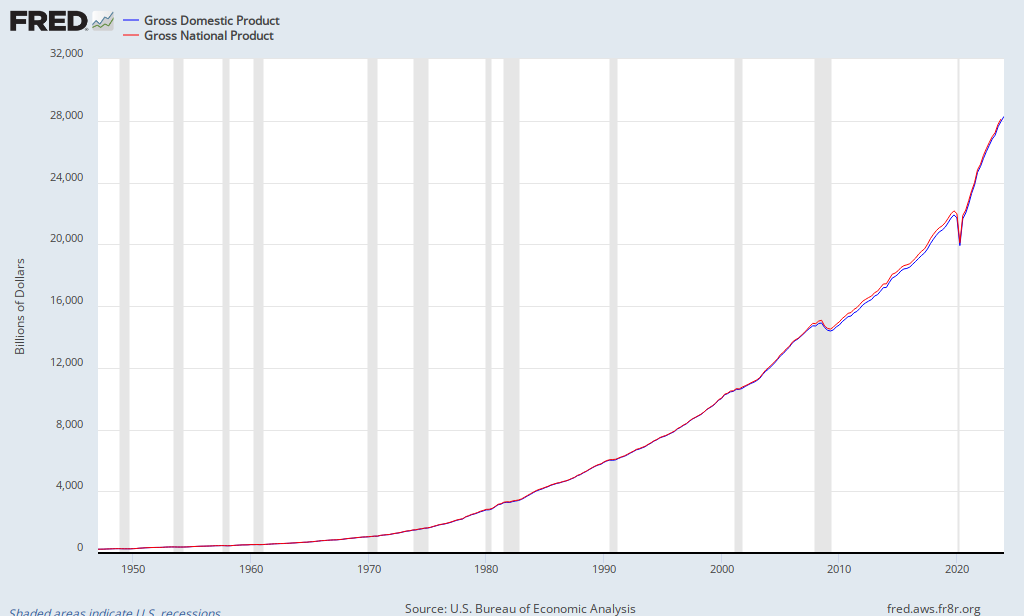

A quick refresher: GDP is “the total market value of goods and services produced within the borders of a country.” GNP is “is the total market value of goods and services produced by the residents of a country, even if they’re living abroad. So if a U.S. resident earns money from an investment overseas, that value would be included in GNP (but not GDP).” While the distinction between the two is important because American firms are increasing the amount of business they do internationally, the actual difference between GNP and GDP is minimal as this chart from the St Louis Fed demonstrates:

GDP in Q4 2012 stood at $15,851.2 billion. GNP at Q3 2012 (the last data point available) stood at $16,054.2 billion. For our present purposes, one substitutes equally as well for the other.

For the market value of all publicly traded securities, we can use The Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index. The index stood Friday at $16,461.52 billion. The following chart updates in real time:

Here are the calculations:

- The current ratio of total market capitalization to GNP is 16,461.52 / 16,054.2 or 103 percent.

- The current ratio of total market capitalization to GDP is 16,461.52 / 15,851.2 or 104 percent.

You can undertake these calculations yourself, or you can go to Gurufocus, which has a series of handy charts demonstrating the relationship of GDP to Wilshire total market capitalization:

Chart 1. Total Market Cap and GDP

Chart 1 demonstrates that total market capitalization has now exceeded GDP (note the other two auspicious peaks of total market capitalization over GDP in 1999 and 2007).

Chart 2. Ratio of Total Market Capitalization and GDP

Chart 2 shows that the current ratio is well below the ratio achieved in the last two peaks (1999 and 2007), but well above the 1982 stock market low preceding the last secular bull market.

But, so what? Is the ratio of total market capitalization to GDP predictive?

In this week’s The Hook (March 25, 2013) Hussman discusses his use of market value of U.S. equities relative to GDP, which he says has a 90% correlation with subsequent 10-year total returns on the S&P 500:

Notably, the market value of U.S. equities relative to GDP – though not as elevated as at the 2000 bubble top – is not depressed by any means. On the contrary, since the 1940’s, the ratio of equity market value to GDP has demonstrated a 90% correlation with subsequent 10-year total returns on the S&P 500 (see Investment, Speculation, Valuation, and Tinker Bell), and the present level is associated with projected annual total returns on the S&P 500 of just over 3% annually.

Here’s Gurufocus’s comparison of predicted and actual returns assuming three different ratios (TMC/GDP = 40 percent, 80 percent, and 120 percent) at the terminal date:

Chart 3. Predicted and Actual Returns

Chart 3 shows the outcome of three terminal ratios of total market capitalization to GDP. Consider the likelihood of these three scenarios:

- A terminal ratio of 120 percent (equivalent to the 1999 to 2001 peak) leads to annualized nominal returns of 8.1 percent over the next 10 years.

- A terminal ratio of 80 percent (the long-run average) leads to annualized nominal returns of 3 percent over the next 10 years.

- A terminal ratio of 40 percent (approximating the 1982 low of 35 percent) leads to annualized nominal returns of -5 percent over the next 10 years.

For mine, 1 seems less likely than scenarios 2 or 3, with the long run mean (scenario 2) the most likely. For his part, Buffett opines:

For me, the message of that chart is this: If the percentage relationship falls to the 70% or 80% area, buying stocks is likely to work very well for you. If the ratio approaches 200%–as it did in 1999 and a part of 2000–you are playing with fire.

Gurufocus’s 80-percent-long-run-average calculation agrees with Hussman’s calculation of average annualized market return of 3%:

As of today, the Total Market Index is at $ 16461.5 billion, which is about 104.3% of the last reported GDP. The US stock market is positioned for an average annualized return of 3%, estimated from the historical valuations of the stock market. This includes the returns from the dividends, currently yielding at 2%.

Here’s Buffett again:

The tour we’ve taken through the last century proves that market irrationality of an extreme kind periodically erupts–and compellingly suggests that investors wanting to do well had better learn how to deal with the next outbreak. What’s needed is an antidote, and in my opinion that’s quantification. If you quantify, you won’t necessarily rise to brilliance, but neither will you sink into craziness.

On a macro basis, quantification doesn’t have to be complicated at all. Below is a chart, starting almost 80 years ago and really quite fundamental in what it says. The chart shows the market value of all publicly traded securities as a percentage of the country’s business–that is, as a percentage of GNP. The ratio has certain limitations in telling you what you need to know. Still, it is probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment. And as you can see, nearly two years ago the ratio rose to an unprecedented level. That should have been a very strong warning signal.

The current ratios of total market capitalization to GNP and GDP should be very strong warning signals. Further, that they imply similar returns to the Shiller PE and Tobin’s q, suggests that they are robust.

Order Quantitative Value from Wiley Finance, Amazon, or Barnes and Noble.

Click here if you’d like to read more on Quantitative Value, or connect with me on LinkedIn.