David Tepper was on CNBC this morning arguing that stocks are historically cheap:

[Tepper] said the post showed “when the equity risk premium is high historically, you get better returns after that.” He continued, “So we’re at one of the highest all-time risk premiums in history.”

In making his argument Tepper referred to this article, Are Stocks Cheap? A Review of the Evidence, in which Fernando Duarte and Carlo Rosa argue that stocks are cheap because the “Fed model”—the equity risk premium measured as the difference between the forward operating earnings yield on the S&P500 and the 10-year Treasury bond yield—is at a historic high. Here’s the chart:

Here’s Duarte and Rosa in the article:

Let’s now take a look at the facts. The chart [above] shows the weighted average of the twenty-nine models for the one-month-ahead equity risk premium, with the weights selected so that this single measure explains as much of the variability across models as possible (for the geeks: it is the first principal component). The value of 5.4 percent for December 2012 is about as high as it’s ever been.The previous two peaks correspond to November 1974 and January 2009. Those were dicey times. By the end of 1974, we had just experienced the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and had a terrible case of stagflation. January 2009 is fresher in our memory. Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the upheaval in financial markets, the economy had just shed almost 600,000 jobs in one month and was in its deepest recession since the 1930s. It is difficult to argue that we’re living in rosy times, but we are surely in better shape now than then.

The Fed model seems like an intuitive measure of market valuation, but how predictive has it been historically? John Hussman examined it in his August 20, 2007 piece Long-Term Evidence on the Fed Model and Forward Operating P/E Ratios. Hussman writes:

The assumed one-to-one correspondence between forward earnings yields and 10-year Treasury yields is a statistical artifact of the period from 1982 to the late 1990’s, during which U.S. stocks moved from profound undervaluation (high earnings yields) to extreme overvaluation (depressed earnings yields). The Fed Model implicitly assumes that stocks experienced only a small change in “fair valuation” during this period (despite the fact that stocks achieved average annual returns of nearly 20% for 18 years), and attributes the change in earnings yields to a similar decline in 10-year Treasury yields over this period.

Unfortunately, there is nothing even close to a one-to-one relationship between earnings yields and interest rates in long-term historical data. Why doesn’t Wall Street know this? Because data on forward operating earnings estimates has only been compiled since the early 1980’s. There is no long-term historical data, and for this reason, the “normal” level of forward operating P/E ratios, as well as the long-term validity of the Fed Model, has remained untested.

Ruh roh. The Fed model is not predictive? What is? Hussman continues:

… [T]he profile of actual market returns – especially over 7-10 year horizons – looks much like the simple, humble, raw earnings yield, unadjusted for 10-year Treasury yields (which are too short in duration and in persistence to drive the valuation of stocks having far longer “durations”).

On close inspection, the Fed Model has nearly insane implications. For example, the model implies that stocks were not even 20% undervalued at the generational 1982 lows, when the P/E on the S&P 500 was less than 7. Stocks followed with 20% annual returns, not just for one year, not just for 10 years, but for 18 years. Interestingly, the Fed Model also identifies the market as about 20% undervalued in 1972, just before the S&P 500 fellby half. And though it’s not depicted in the above chart, if you go back even further in history, you’ll find that the Fed Model implies that stocks were about as “undervalued” as it says stocks are today – right before the 1929 crash.

Yes, the low stock yields in 1987 and 2000 were unfavorable, but they were unfavorable without the misguided one-for-one “correction” for 10-year Treasury yields that is inherent in the Fed Model. It cannot be stressed enough that the Fed Model destroys the information that earnings yields provide about subsequent market returns.

The chart below presents the two versions of Hussman’s calculation of the equity risk premium along with the annual total return of the S&P 500 over the following decade.

Source: Hussman, Investment, Speculation, Valuation, and Tinker Bell (March 2013)

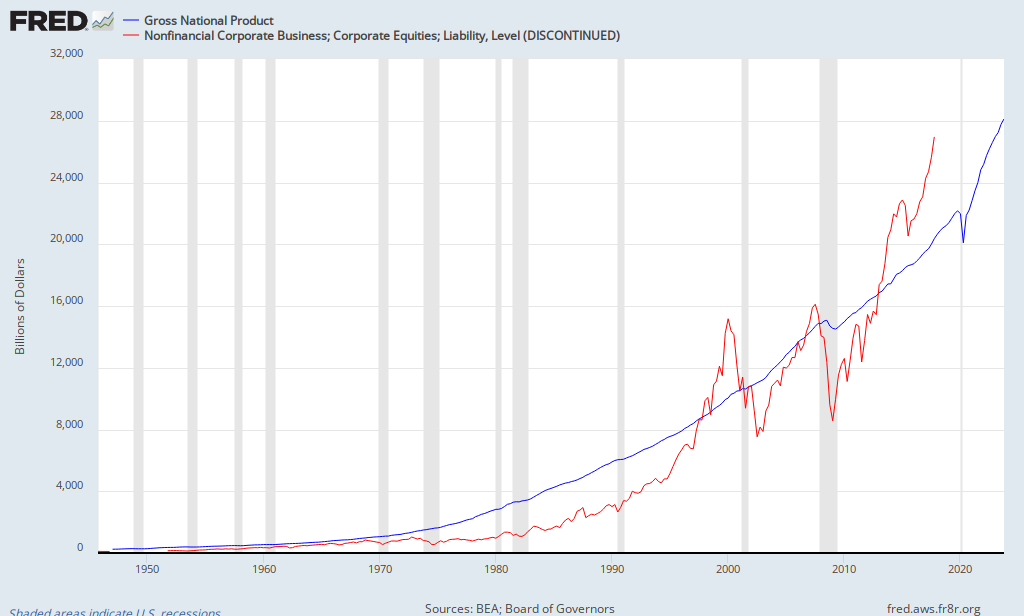

That’s not a great fit. The relationship is much less predictive than the other models I’ve considered on Greenbackd over the last month or so (see, for example, the Shiller PE, Buffett’s total market capitalization-to-gross national product, and the equity q ratio, all three examined together in The Physics Of Investing In Expensive Markets: How to Apply Simple Statistical Models). Hussman says in relation to the chart above:

… [T]he correlation of “Fed Model” valuations with actual subsequent 10-year S&P 500 total returns is only 47% in the post-war period, compared with 84% for the other models presented above [Shiller PE with mean reversion, dividend model with mean reversion, market capitalization-to-GDP]. In case one wishes to discard the record before 1980 from the analysis, it’s worth noting that since 1980, the correlation of the FedModel with subsequent S&P 500 total returns has been just 27%, compared with an average correlation of 90% for the other models since 1980. Ditto, by the way for the relationship of these models with the difference between realized S&P 500 total returns and realized 10-year Treasury returns.

Still, maybe the Fed Model is better at explaining shorter-term market returns. Maybe, but no. It turns out that the correlation of the Fed Model with subsequent one-year S&P 500 total returns is only 23% – regardless of whether one looks at the period since 1948 (which requires imputed forward earnings since 1980), or the period since 1980 itself. All of the other models have better records. Two-year returns? Nope. 20% correlation for the Fed Model, versus an average correlation of 50% for the others.

Are stocks cheap on the basis of the Fed model? It seems so. Should we care? No. I’ll leave the final word to Hussman:

Over time, Fed Model adherents are likely to observe behavior in this indicator that is much more like its behavior prior to the 1980’s. Specifically, the Fed model will most probably creep to higher and higher levels of putative “undervaluation,” which will be completely uninformative and uncorrelated with actual subsequent returns.

…

The popularity of the Fed Model will end in tears. The Fed Model destroys useful information. It is a statistical artifact. It is bait for investors ignorant of history. It is a hook; a trap.

Hussman wrote that in August 2007 and he was dead right. He still is.

Order Quantitative Value from Wiley Finance, Amazon, or Barnes and Noble.

Click here if you’d like to read more on Quantitative Value, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

Read Full Post »